“I was beginning to wonder if I should send out a search party,” says Cindy, as we arrive at the White House B&B in Newnham, to the east of Baldock. “Where have you two walked from, again?”

“Cambridge. But that’s not the half of it,” I say, remembering Cindy’s response – “Goodness, that was not what I was expecting!!” – to my explanation for not being able to be more specific with regards to when we might arrive.

“This is Day One of ten,” adds Rob. “We’re walking to Cardiff.”

I never got tired of the look on people’s faces.

“Why?” asks Cindy.

It’s a question I still can’t answer.

***

It’s Day Ten. Somewhere to the west of Newport, Rob and I are approaching our 200th mile. I ask if he remembers the genesis of the idea to walk to Cardiff. Memories are hazy, but at some point – in the Autumn? Over Christmas? New Year’s Eve? – there was talk of how nobody calls on anybody anymore. Wouldn’t it be funny if we called on Tom and asked if he wanted to come out and play? If he fancied a pint in his pub, The Lansdowne?

I fish my phone out of my pocket, scrolling back through our WhatsApp chat. It only goes back to October, when I got a new phone, but here we go:

Most people assumed we were doing it for charity. Maybe we should have been, but the truth was that we weren’t. We didn’t need the commitment device. Walking to Cardiff appealed to our sense of the epic and the absurd, and we were doing it because we could. That’s could in the sense that we had permission – Gemma, Rob’s wife, granting him ten days leave.Whether we could physically – well, there was only one way to find out.

Rewind four years, and the idea of walking anywhere would have seemed impossible. The simple task of putting on socks and shoes was enough to bring a tear to the eye. I’d had back trouble before, but this was serious. My body was beyond hope, and my mind was all too ready to agree. What did it say about my life when I had always taken the view that fitness – like a suntan – is a by-product of doing something more interesting? I’ll run after a ball or to score a run, but I can’t Go For A Run. Not without a voice in my head screaming this is boring and painful. Likewise, I’ve never been to a gym in my life. Life is repetitive enough without lifting things up and running on a treadmill. But I couldn’t play football or cricket to get fit, as an abortive net session confirmed, and I couldn’t even ride my bike. I was stuck in this miserable debilitating existence – until, that is, I started walking.

Rob can also attest to the power of a daily walk in the struggle against bad backs, but neither of us had done anything like this. I’d discovered the step counter on my phone during a month in India in 2016, and become mildly obsessed with it in the summer of 2018, when walking off my bad back. Time to rekindle that obsession. The daily step counts went up, but we really needed a training day. Three more followed in the next couple of months, but that first training day in early February – a 22-mile circular walk along the Roman Road and Fleam Dyke – proved that we could do it. With T-Man along for the ride, we learnt some vital lessons along the way: waterproof shoes would be useful; lunchtime pints less so; there is no such thing as a bad biscuit; the last mile is the hardest.

***

It’s late on Day Two. My feet are on fire, but I’ll be fine once I’ve taken a load off. That pint of Guinness is going to taste so good. I’ll be a new man after a shower, a square meal and a good night’s kip. I’m getting ahead of myself – which is precisely why the last mile is the hardest. To be fair, the preceding six miles – skirting along the very edge of Luton – haven’t been that easy. Look to the left and it’s a housing/industrial estate. Look down and it’s fly-tipping and dog tod. A soundtrack of traffic drone, the M1 getting ever closer. All this, and a Friday night in Dunstable as an incentive.

There’s been nowhere to sit down and take a break for ages, so – just a mile or so from our destination – we decide to stop at Houghton Hall Park. We’re nearly there when I feel the unmistakeable hot squelch of a blister bursting on the bottom of the little toe of my right foot. A fear grips me. I couldn’t quit, could I? Not in Dunstable. Not after just two days. This was never a competition between us, but a part of me is thinking: I can’t lose to Rob. Not Rob, the least competitive and least sporty person I know. Not Rob, who had sat in his car smoking B&H while the rest of us played football, the first time I met him.

The first day had seemed so easy. Sure, the bags we were carrying were a reminder that we would have to get up and do this all again for another nine tomorrows, but there was the sense – exacerbated by the unremarkable and somewhat familiar route – that this was one last training day. With Rich providing welcome company (T-Man having succumbed to a positive Covid test), it felt like we were deferring the moment that Rob and I embarked on our adventure.

A day later and shit had got real.

***

Shit had seemed very abstract back in the planning days. We had somewhere to stay in Oxford – Tom’s dad’s place – and a pretty good idea of the route, thanks to the online discovery of Ordnance Survey maps for a ‘Varsity March’ from Oxford to Cambridge in 2015. The Cambridge University Ramblers Club did the 81 miles in a weekend, but – going by Rob’s calculations – we could do the reverse journey in four days. We could then follow the Thames Trail and, once over the border – the old Severn Bridge catered for pedestrians – we could take up the Wales Coastal Path. Even when we had booked accommodation, it was just names on a map. Newnham, Dunstable, Aylesbury, Oxford, Radcot, Cricklade, Didmarton, Aust, Newport, Cardiff. Easy to trace a finger over a screen, but could we walk the walk?

***

The last mile is the hardest, but we make it – thanks to a change of footwear on my part – to our accommodation in Dunstable. Slumped on a step as Rob checks us in, I don’t care that I stink. I’m too tired to worry about how incongruous I must look to all these people, or to wonder what event they’re attending. The strange alchemy of the end of a day’s walk has yet to kick in. Fatigue has yet to mix with relief and satisfaction, but a catalyst is to hand in the form of a doppelgänger for our friend Matt. A shower and that pint of Guinness help, too.

We’re staying at the Old Palace Lodge, which is neither old nor palatial, but one out of three is enough for us weary travellers. It’s a reminder that this is an adventure, that we can never know what’s round the next corner. You can imagine what Dunstable on a Friday might be like, but until you’ve walked past a bouncer outside an empty pub, you can’t know. Not until you’ve discovered that everybody – for good reason – is crammed into Lumpini Thai Restaurant.

After two days on the road and two years of Covid restrictions, it’s slightly unnerving to be surrounded by so many people. But it’s Covid that’s brought us here, really. After all, if it hadn’t been for my experiences on the retail frontline during the pandemic, I’d most likely still be stuck in the same old boring job. Those fraught first few months of Lockdown were exhausting. It wasn’t just the physical labour of serving a never-ending (socially distanced) queue of people needing their five a day, it was being in a state of hyper-awareness – alert to every breath and every touch – that made it so tiring. But on the other hand, it was energising. I had a purpose. There was value and meaning to be had – even pride – in selling fruit and veg. I was a Key Worker. Doing the same job that had often left me wondering why I was getting paid to do the crossword and listen to Test Match Special. As much as a return to normality would have come as welcome relief from the new normal, I knew I couldn’t go back. After all, I’d only agreed to work in the shop for a fortnight, while I looked for a Proper Job. Getting on for twenty years later, I sold what I told myself would be my last ever Christmas tree. I thought of Steve Redgrave – “I’ve had it. If anyone sees me near a boat, they can shoot me” – and wondered if I was a man of my word. The conviction endured – hardened, even, over the harsh winter Lockdown – and last July, with the world opening up, I told my boss I was leaving. With three months notice, I was getting out before the shop went back to self-service and before the clocks went back. I’d get to enjoy Christmas. I’d get to go fully nocturnal and watch the Ashes. I’d get to enjoy the privilege of not having to work, of taking the time to work out what I might want to do next. I’d get to … walk to Cardiff.

***

I thought I’d broken in my walking boots. Sure, they’d given me blisters to start with, but that was months ago. I’d walked miles since then with no issue. The trainers were an afterthought, the last thing I packed. Them or slippers – something comfortable to wear in the evenings. Thank goodness I made the right choice. And eternal thanks to my brother for introducing me to the world of Compeed blister plasters. There’s goodness in those little aquamarine boxes. But they’re hard to come by on a Saturday morning in Dunstable. We’re keen to get going – have been since getting woken up at four a.m. by sex people in a neighbouring room – but Boots in the Quadrant Shopping Centre doesn’t open til nine. Doesn’t open at nine, either, and it’s a pretty bleak place to be waiting. We find another pharmacy and I get my early morning Compeed hit, sitting on a bench outside the police station. I want arresting, but I’m good to go.

Sometimes you have to moan,

when nothing seems to suit ya

Nevertheless you know,

you’re locked towards the future

So on and on you go,

the seconds tick the time out

There’s so much left to know,

and I’m on the road to find out

On the Road to Find Out, Cat Stevens

Any illusions I had about this being a holiday have disappeared. This is a mission. A mission I now have a burning desire to complete. The fire in my feet has spread, a spark has ignited something in me. Rob and I have both subsequently read Trespassing Across America by Ken Ilgunas, the book Rob carried to Cardiff, and the following description of an Alaskan (mis)adventure rang a bell: “Such unpleasantness can function as a restorative distraction, a resuscitating shock, a defibrillator charge to the soul.”

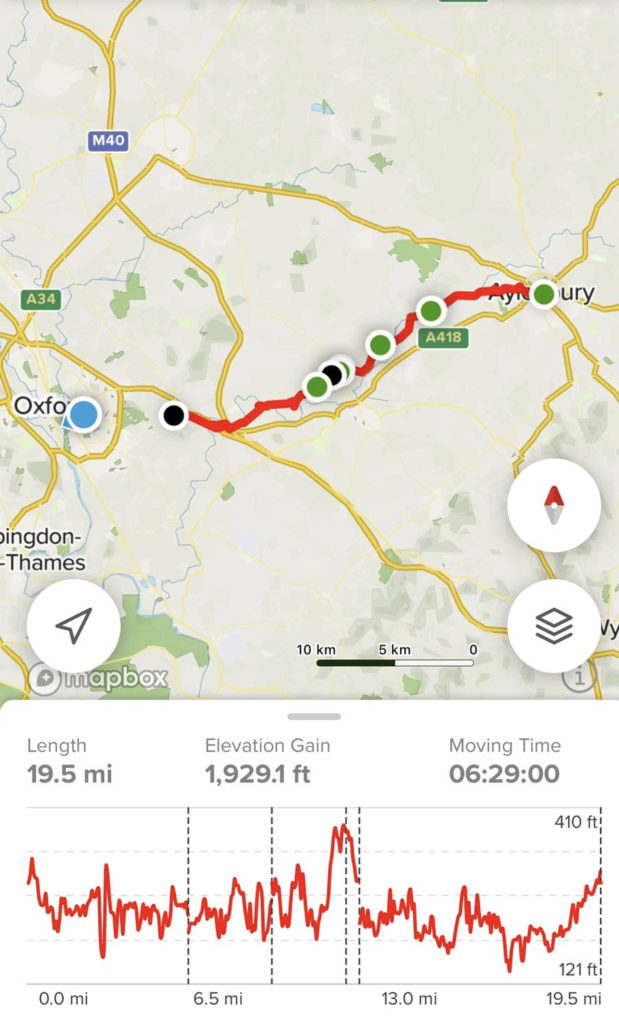

As if to mock me for my hubris, my toe’s path for most of Day Three will be the towpath of the Grand Union Canal. Still, the going is firm, the weather glorious. We’ve survived Dunstable and – at a mere eighteen miles – this is one of the shorter days. It’s mad to think that this quiet waterway, this feat of engineering with its series of locks and bridges, could have ever played such a significant role in the history of the world. Even this branch that goes to Aylesbury, our home for the night and another place we know nothing about. Rob asks the young lad on reception at the Travelodge for a recommendation on where to go for a drink. It isn’t clear whether his response – “I don’t really go out” – is a reflection on him or his town. We settle on Wagamama. Afterwards, eating vending machine ‘bed dessert’, watching Eurovision, we could be anywhere. But we’re not. We’re in Aylesbury, and we’ve walked for three days to get here.

A slight hitch in Hitchin aside, navigation has thus far been relatively straightforward. Day Four – the long slog to Oxford – is about to change all that. It could have been worse. I’ve already discovered, wading through chest-high cow parsley, that what my trainers make up for in comfort, they lack in waterproofness. Now there’s a metal fence barring our path, a map giving directions for a three mile diversion. Before we have time to contemplate our fate, a dog walker on a bike tells us of a hole in the fence. “Follow me,” he says. What does it say about modern life that these experiences, when a stranger is trusted explicitly, are so rare? And what does my trepidation, however slight, say about me? Still, a lesson in the kindness of strangers is a nice way to re-up my faith in humanity, and we’re relieved to be back on track.

A public footpath is a wonderful thing. A rare public asset in an increasingly private and privatised world. But some are more public than others. Some are permissive paths, dependent on landowners for maintenance. It’s a task that some landowners take more seriously than others. Like in the fields around the Buckinghamshire village of Shabbington, where the landowner has chosen to make every gate different, its own bespoke puzzle. It’s like being in Taskmaster. More generally, there’s usually a signpost pointing the way, but sometimes there’s no semblance of a path. Which brings us to Junction 8a of the M40. It’s been a long day, and we’ve already had to dig out the waterproofs for the first time. The map says there should be a footpath that takes us through a field and then under a bridge. Sure enough, there’s the signpost. Down these stairs. These stairs, overgrown with brambles, that nobody has used in a long time. There’s no sign of a path across the field, but in the far corner there’s the bridge. A bridge, it turns out, with knee high slurry and a gate barring our way. Our only option is to trudge back through the soggy crops and try to cross the dual carriageway. We make it across, but the sight of cars driving towards Oxford on the A418 is enough to get Rob thinking about ordering a cab.

***

“Well done,” says Gemma, dropping me home the day after we arrived in Cardiff. The return journey has been somewhat easier, it has to be said. “And thanks for putting up with my husband,” she adds.

“Thanks,” I reply. “And well done, you, for coping without him. I know I couldn’t have done it without him.”

“Likewise, pal,” says Rob. “Without you, I’d still be halfway up a hill outside Oxford.”

***

There’s no proof that we didn’t get a cab. Rob’s AllTrails app wasn’t just a handy navigation aid – it also mapped our journey. The map for Day Four is incomplete, the red snake doesn’t reach the blue dot. Only Rob and I know why. Only Rob knows how close his own battery was to running out halfway up that hill, as his phone had done. And I’ll never know how I managed to find my inner Mr Motivator. The truth resides in our calf muscles and our hearts, but we made it. Up the hill, across Shotover Country Park and down Shotover Hill into Oxford.

We’re due to join the Thames Trail on Day Five, but that can wait. Firstly, for some emergency early morning podiatry on a bench on Magdalen Bridge, and then because we can cut a corner. By this point, we’re more concerned with how the crow flies than with how the river cuts its meandering course. We join the Thames after crossing a courseway over Farmoor Reservoir. But not for long, it turns out. The Thames Trail instead cuts across fields full of flighty sheep, where we realise we have walked one hundred miles. There’s a pub where the path rejoins the Thames. We’ll have to have a celebratory drink. Outside. Because the Ferryman Arms is not the idyllic riverside pub of our imaginations. It’s more of a caravan park-side pub, and judging by the signage, not very tourist-friendly. It’s my round. In terms of decor and ambience, my only frame of reference will only make sense to anyone who went to the Master Mariner on Perne Road in Cambridge in the late 90s.

Still, we’re seeing the river at its spring best. After the morning’s lambs, it’s now ducklings and goslings. Surrounded by so much vitality, it’s hard not to feel alive. This is the bit of the walk that I’d been looking forward to most, and the wilderness is every bit as beautiful as I’d imagined. But for all that, it soon becomes a bit monotonous. No real landmarks, nothing to aim for on the horizon. Just the next gate, the next field – another million buttercups dancing in the wind. With the yellow flowers and the blue sky, it’s like walking through a giant Ukrainian flag – the river acting as a flagpole.

Perhaps, rather than the countryside, it’s the walking itself that is monotonous. Maybe the hundred mile mark came with a realisation that we’re only approaching the half way point. We stop for a soft drink at the Maybush in Newbridge. It’s quite the contrast to the Ferryman. Noticing the popularity of the food, we decide to have a late lunch. Back underway, Rob lightens the mood by digging out his speaker. He also manages to drop his Thames Trail guidebook in the Thames. Not on purpose, but it soon turns out – when I discover Rob had sent me pictures of all the maps – that it wouldn’t have been a hindrance to our progress if he had. The Thames Trail is well signposted, in any case. Walking through clouds of mayflies, hissed at by protective geese, and picking our way through a field filled with a truly hallucinatory amount of cows, we make our way to Radcot.

Ye Olde Swan in Radcot – with its log fire, interesting and interested locals – is a great pub. With the caveat that I might not be at my most objective, it also has an excellent pint of Guinness. But it doesn’t serve food on Mondays. Good job we had that late lunch. And good job our Air B&B host – a mile down the road – has put out stuff for breakfast in advance. Cereal, crumpets, a massive sour dough loaf. And there’s a biscuit tin, too, with the following written on the lid: ‘If you feel something is missing in life then it is almost always a biscuit’ They saw us coming. In the morning, my feet don’t want to leave. Bathroom tiles have never felt so cooling, carpet has never felt so luxuriant.

***

Talking to friends after it was all over, a common question has been whether we ran out of chat. The answer is yes, at times, inevitably. But Rob and I have never been ones for small talk, so the silence was always companionable. Besides, walking over new ground brings its own distractions and stimuli, its own absorption. And when it’s shared, sometimes nothing needs to be said. Seeing is enough, experiencing is enough.

That said, there’s a sense on Day Six that we have seen enough of the Thames, so listening to Flight of the Concords comes as welcome relief. As does a much shorter day, meaning we arrive at The Old Bear in Cricklade at 5:30 – a good two hours earlier than we had reached Radcot, and about ten minutes before it starts raining. Timing. It turns out 5:30 on a Tuesday is a good time to enter a pub, looking windswept and interesting. The old boys enjoying an afternoon pint or two are keen to know what we’re up to, and tip us off that the Red Lion is the place to eat. They’re not wrong. ‘Never trust a skinny chef’ reads a sign near the kitchen, and this chef must be a big old boy/girl. The quantity is matched by the quality, and after three courses we can barely walk. Or finish our pints back at The Old Bear, where we are staying in a converted stable.

“Excuse me. They’re scared of you.”

They are two horses and, according to one of the middle-aged ladies walking them, it’s Rob and I that are scary.

She tries to explain: “Hiding in the bushes. With those bags on your backs, and that hat.”

This hat? This wide-brimmed cricket hat? This is a horse-scaring hat? And besides, we weren’t hiding. We were debating whether to take that public footpath, mindful that we don’t want to get our feet wet.

“Sorry,” says Rob. “Are we right in thinking this road goes to Minety?” he asks, more in the hope of learning how to pronounce the name of the Wiltshire village than how to get there.

“Minety?” – it rhymes with ninety – “No, you want to go back that way.”

Thanking them for their help, we wait until they’re out of scaring range. Consulting his phone, Rob confirms that we’ve been sold a lie. We proceed along the same road, some fifty yards behind the horses. The road turns into a path, at which point the horse ladies stop before turning their steeds around, heading back the way they came. I take off my hat and make a point of giving them a wide berth, as we take the path. The path that leads to Minety. Quite why we couldn’t have been told that twenty minutes ago is unclear.

From Minety we stick to roads, stopping for lunch in Malmesbury. Time to check on those feet. It’s been a week since that first blister. Safely covered under a couple of Compeeds, that little piggy is probably on the mend – could probably be peeled liked a banana. But he was just the start. As was the equivalent on my left foot. Other toes have had to take up the strain. The second runtiest pig on my right foot, in particular. It’s Day Seven, and Rob is also now suffering.

Back on Day Three we had enjoyed a couple of beers at the Red Lion in Marsworth, discovering that it’s impossible to tear open a bag of crisps if you think about it. Try it, next time you’re sharing a bag in the pub. You’ll be surprised how much thoughts can get in the way of acts. It’s the same with walking. Starting again is difficult, and the sight of two middle-aged men trying to remember how to walk must make for an odd spectacle. But once we remember which bits of our feet to avoid landing on, a rhythm can be achieved. Walking becomes as much of a conscious act as breathing. Life is just a process of getting over your self, and there’s something about the meditative act of putting one foot in front of the other that quietens the mind. Is it mindfulness or mindlessness? Whatever, self-consciousness can’t keep up.

Clocking in at nearly twenty-six miles, it’s a long day, but we make it to Didmarton. As per the previous night, we’re staying at a pub and we arrive just before the rain. There are worse places to take shelter than The King’s Arms. Only two courses tonight, though.

Back at our digs, we watch Prince of Muck, a documentary about the Scottish island of Muck and its owners, the McEwen family. It’s being repeated because the star of the show, Lawrence McEwen, has recently passed away. There’s a poignant scene towards the end when the elderly Lawrence, walking slowly back to the farmhouse, is overtaken by his son – now in charge of the family farm – on a quad bike.

The following day, as we make our way to Aust services, where the Travelodge in which we’re staying is located, the scene comes back to me. Unless you’re Alan Partridge singing Goldfinger, motorway services aren’t designed to be reached on foot. Aust, where the old Severn Bridge will take us to Wales, is no different. I’ve never been a fan of cars, but after eight days of walking, they feel like an affront to the natural pace of things, a breach of the peace.

It’s an observation I could have made first thing in the morning, as we trudged beside the A433 out of Didmarton. But I’d been more concerned with wet feet, a cracking headache and the fact that I’d been sick. If the verges of Aust are a reminder that the last mile is the hardest, this morning was the exception to another rule. The first five miles are the easiest. Most days, the discovery that we’d done five miles comes as a shock. Already? But Day Eight wasn’t most days.

Aust Travelodge is euphemistically called Severn View, but Car Park Vista might be more appropriate. It’s Rob’s turn to buy dinner. Service station tapas from a choice of Costa, Burger King and WH Smith. I don’t know if I’m more disappointed in myself or the Chicken Royale meal. There’s a chance I might be sick again – with self-disgust. I jest, because I actually feel like a new man. Have done since Hawkesbury Upton, and the moment I noticed a cracking name on the village war memorial. Herbert J Niblett. Patron Saint of hangover cures. Shortbread has never tasted so good. Water has never been so refreshing. Ibuprofen has never kicked in so quickly. Is it me, or are my feet on the mend?

Bookended by unpleasantness, it’s actually been a great day. Sunshine. Two episodes of the Adam Buxton Podcast. A pub lunch in Tytherington. Our first glimpse of the Severn Bridge. This response from a pharmacist in Alveston: “I don’t even know where Cambridge is, but it sounds a long way away.”

Feels it, too. And Cardiff, just over the bridge, is still two days away.

“Breakfast,” says Rob, handing me a cardboard box he’s collected from reception. It’s a far cry from this time last week, when we were sitting down to Cindy’s cooked breakfast. We’ve come a long way since then, and it’s taken its toll. Most obviously on our feet, but Rob has woken up with a rash all across his back. Heat rash from eight days of carrying a sweaty rucksack. Mindful of wanting to arrive in Cardiff with enough energy to celebrate, we talk of maybe getting a train to Newport.

In typical drizzle, we cross one Severn Bridge and go under the other, winding our way along the coast to Caldicot. We’ve walked to Wales. No shame in getting a train. We’ll still break two-hundred miles by the time we get to Cardiff. No shame in that. The shame would have to wait.

No regrets, then, but it’s still possible to think what we might do differently if we had to walk to Cardiff again. Apart from be preemptive with the Compeeds, that is. And get a comfier bag. Rob and I came to the conclusion that fifteen miles is the perfect distance for a day’s walk. Long enough without being too long, and with more scope to explore. Which brings us to Newport. It doesn’t do any good to think of all the beautiful and interesting places we have hurried through or passed obliviously by. It’s Newport where we’re suddenly blessed with all this time. A place left behind by time. Post-industrial, post-Brexit, post-Covid. Pre-what, though? Levelling up? Yeah, right.

On top of the rash, Rob’s ear is now bleeding. But it’s okay, because we’re sitting in what he has termed a Haven of Shame. We’d later have dinner at another – Wagamama – but for now we’re sitting outside a Starbucks in a retail park. It’s easy to see how people fall for the safety and familiarity of multinational companies. I used to think it was down to a lack of imagination, but now I’m thinking the opposite might also be true. Perhaps sticking with what you know is down to imagining the worst in what you don’t know. In that spirit, Rob decides that he hasn’t got Walking Plague – he’s just scratched a bite.

“I wanna be a flair barman, see. Serving cocktails at some kind of super club.”

Well, you have to start somewhere, I suppose. Under the shadow of Newport Transporter Bridge, the Grade 2 listed Waterloo Hotel is under new management and our barkeep – a Sikh lad from Swansea – is the owner’s son, looking after the place for the weekend. As far as we can tell, we’re the only patrons. We’re certainly the only people in the bar, and our days of going to super clubs are over.

There was never a time when Rob and I fell out of step, no morning when one was waiting impatiently for the other. And Day Ten, when we leave Newport at 6:45, is no different. We’ve worked out that stopping for lunch after half way is the way to go, but at this rate – a pace not seen since Day One – we’ll be in Cardiff by lunchtime.

We throw off our bags, by now consisting almost exclusively of dirty clothes, and slump to the ground. It may not be apparent to any onlookers, but they are triumphant slumps to the ground. We’re in Bute Park, the Welsh flag flies proudly from Cardiff Castle. Rob passes me a can of Guinness. Cheers. A quiet half hour before we head to the Lansdowne, a last half hour together as comrades, as companions. None of this gets said, of course, because we’re ruddy bloody blokes, but I’ll miss it. I’ll miss having someone else to give a shit about. What is life, after all, but a journey shared?

It’s not the destination, it’s the journey. After walking roughly 210 miles across ten days and nine counties, we’re ready to accept it’s both. The Lansdowne doesn’t disappoint.

The celebrations carry on back at Tom and Cerys’ house. At some point late into the night, I can stay awake no longer.

“Props,” says Tom.

He reads the grin that breaks across my face.

“You idiot,” he adds.

The grin was one of satisfaction, but it also spoke to the absurdity of walking from Cambridge to Cardiff.

“Idiot props,” I say. “I’ll take that.”